The Life and Death of a Soldier

Our son was an incredible soldier, son, brother, grandson, uncle, cousin, husband, patriot, nephew, American. A sniper took his life March 21, 2007 in Baghdad, Iraq.

E-Mails Reveal a Fallen Soldier's Story

By Alex Kingsbury | Posted 5/13/07 (U.S. News and world report.)

Four days before his death, Army Staff Sgt. Darrell Ray Griffin Jr., an infantry squad leader in Baghdad, sent an E-mail to his wife, Diana. "Spartan women of Greece used to tell their husbands, before they went into battle, to come back with their shields or laying on them, dying honorably in battle. But if they did not return with their shield, this showed that they ran away from the battle. Cowardice was not a Spartan virtue ... Tell me that you love me the same by me coming back with my shield or on it."

A few days later, Diana replied. "Are you ok??? I haven't heard from you since Sunday and it is now Wednesday ... I know you said you were going on a dangerous mission ... I get so nervous when I don't hear from you ... phone call or e-mail ... I just hope and pray your ok honey ... "

War is dirty

It was an E-mail Griffin would never read.

As the Baghdad security plan draws thousands more troops into densely populated parts of the Iraqi capital, the danger from roadside bombs and small-arms fire grows exponentially. The city has now surpassed Anbar province as the deadliest region for U.S. troops. Since the war began, more than 3,370 American soldiers and marines have been killed and more than 25,000 wounded in Iraq, and, in terms of American casualties, the past six months have been the costliest of the war. American commanders say they expect casualties to increase in the next three months.

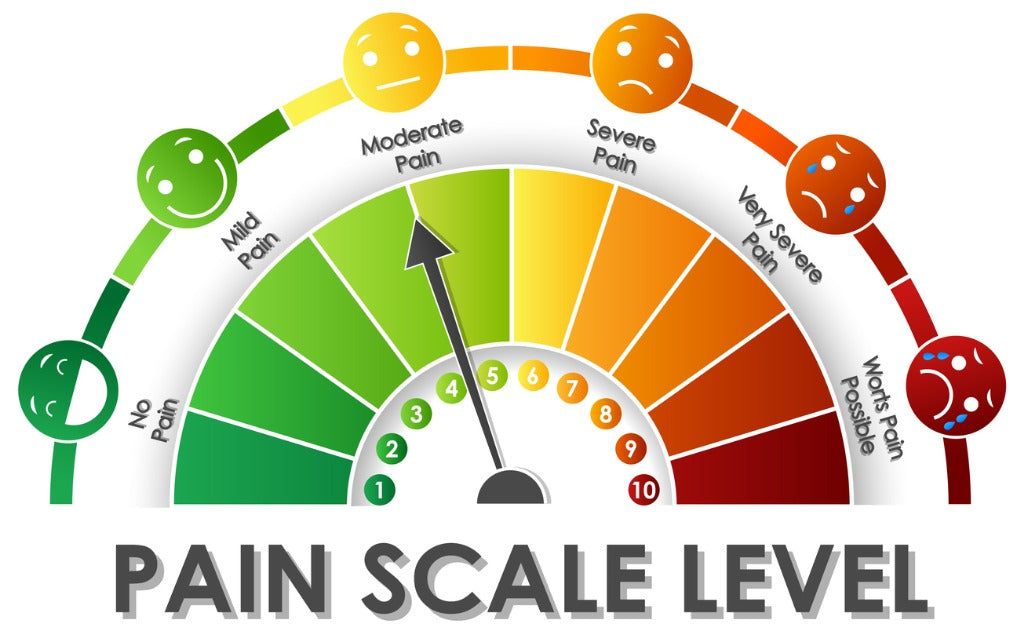

One of those casualties was Darrell Griffin, felled by a sniper's bullet on March 21, 2007, while patrolling in Sadr City. He was fatally shot while standing in the hatch of a Stryker armored vehicle. I interviewed him on March 3, 10 days before his 36th birthday, at a forward operating base near the town of Iskandariyah, 35 miles south of the city where he was killed. The desert sun was bright, and he wore a pair of dark glasses, which covered his eyes but couldn't conceal a spasmodic muscle tic in his face. He was quite self-conscious about the tic, he confessed, but shrugged it off. "That's what happens after two combat tours in Iraq." We talked about a recent battle and about his collection of digital photographs chronicling his two tours in Iraq. He'd seen things, he said, that he could never tell his wife or family on the phone.

We had met the day before, inside a dusty green tent on the base. It was about 10 o'clock on a Friday evening, and the men of Charger Company's 3rd platoon, 2-3 Stryker Brigade, were preparing for a mission to nab a local suspected troublemaker who was holed up in a farmhouse outside of town. Griffin was a big guy, even without the bulky body armor, helmet, and "dangle"—what soldiers call the bits of gear that they clip, strap, or otherwise buckle to their uniforms. He had half a dozen rifle magazines strapped across his chest, two radios, a medical pack, a flashlight, a digital camera, and a variety of other pouches and pockets swollen with kit.

His rifle stock had a sticker of a white skull, and on his helmet written in black Magic Marker was the phrase "Malleus Dei," the Latin phrase meaning God's hammer. During his first tour with a different infantry unit, it was John Calvin's motto "Post Tenebras Lux"—after darkness, light. As he fiddled with all his equipment, he talked about the upcoming mission—how it was likely to be routine, how much things in Iraq had changed since his first deployment, and how the folks back home simply couldn't understand the chaos and carnage that soldiers see on a daily basis.

Embedded with Griffin's unit from the last days of February into early March, I met many of the soldiers in Charger Company. Griffin was a veteran in the unit and more than willing to chat about all he had seen. We mostly talked about a fight near the city of Najaf just a few weeks earlier. Assigned to recover the wreckage of a downed Apache helicopter and the remains of the two pilots, the 2-3 stumbled across what the Army called a Shiite doomsday cult known as the Heaven's Army, which had amassed hundreds of fighters and hundreds of civilians in a compound on the outskirts of town. The 2-3 dug in and called in airstrikes against the buildings, a bombardment that lasted into the wee hours of the morning.

The men spoke often about Najaf because memories of the engagement were still disturbingly fresh in their minds. Hundreds had been killed or maimed, including women and children. The 2-3 didn't lose a man. "Not even a sprained ankle," said Lt. Col. Barry Huggins, the American commander of ground forces at the scene. But several men were still having nightmares—a 19-year-old medic had dreams of treating a child with a missing limb. "And I have lots of photographs of what happened," Griffin offered that evening. "You should sit down and have a look at them." So we sat on his cot, and he began narrating.

There were hundreds of pictures, documenting his two tours with the Army's new Stryker brigades—crack units equipped with the newest vehicles and assigned to some of the toughest missions. We made it through only a few dozen pictures of the battle of Najaf and its bloody aftermath before it was time to go out on the raid, but we agreed to pick up it up again the next day.

The raid was unremarkable. Griffin and his unit failed to nab their target, and the platoon—with a reporter and photographer in tow—spent a few hours chasing five men who had fled the scene across open farm fields. Crunching through those fields, Griffin and I began talking about philosophy and politics and famous thinkers. He hadn't been to college, but he read widely and spoke with a remarkable clarity and urgency about what he had seen. The next afternoon, Griffin again opened his laptop. "I'd like you to copy these pictures and make sure that people see them," he told me. So I plugged my iPod into his computer and began downloading several gigabytes' worth of folders with titles like "SECOND DEPLOYMENT," "ELECTIONS," "TAL AFAR DEATH PICS," and "CLOSE CALLS."

"Would you like to see a picture of the first guy I had to kill?" he asked. It was taken at 12:33 p.m. on April 21, 2005, according to the time stamp. The young man lies dead, covered in blood and dressed in a blue sweater and white jacket.

Then there were pictures of the clash in Najaf in late January, with panoramic shots of the rows of weapons that were seized and the rows of corpses. "I'd never seen anything like it," Griffin said. "The destruction was almost biblical." He wrote about that battle, too.

"My squad and I along with my platoon leader 1LT Weber established a strongpoint at the first corner that we approached. I noticed a mutilated child thrown against a wall from random bomb blasts and as I was setting my machine gunner for security, a man was trying to get out of the village with a dead baby in his arms, holding her as if she was still alive along with his wife who could barely walk because her face had been torn open by the bombing. As this all happened at the same time, a man brought a young 10-12 year old boy to me in his arms and it was obvious that the child was barely breathing but still alive. He tried to hand this child to me but I did not want to take my eyes off of all the villagers who were now approaching my position in droves. The man knew that this boy would die so he placed the boy next to a man whose legs had been blown off lying across from me and in the arms of a dead man this boy finally died. I witnessed so much carnage on this particular day that words and descriptions of the horror would become trivial in attempting to paint a picture of what I saw ..."

"I achieved my 8th confirmed kill in this village when I opened a door to what I thought was just another small room and upon entering, saw human bodies strewn on the floor, wall to wall, that had been placed there because the room had obviously been established as a casualty collection point. One man lying close to the door had been pleading for me to help him and kept pointing to his injured leg. I did not want to commit to entering the room because I had a blind spot to my front left and did not want to be engaged by any survivors; the room was strewn with massive amounts of AK-47's, magazines, grenades and other assortments of weaponry. I motioned for the man to crawl out and he would not or could not comply. He then looked dead into my eyes and suddenly began to smile at me while he reached for his AK-47. I lifted my rifle and fired 8 rounds into his forehead from about 3 feet killing him instantly ..."

"There was so much sensory overload as to the horrific that I was forced to make my squad work in cycles stacking bodies so that they would not have any mental breakdowns. Our local [Iraqi] interpreter "Ricki" even vomited from seeing this macabre spectacle. I knew that as U.S. forces in Iraq, we were definitely now in an even more unpredictable and unstable environment than I had thought prior to this."

After the battle, they found stores of food and ammunition, 11 mortar launchers, and an antiaircraft gun inside the compound. There were so many enemy weapons that the Army filled three pickup trucks with captured guns. More than 200 people surrendered in the morning, and more than 250 were reported killed. "We shifted from secure helicopter, defense, to hasty attack, to clear the trench, to humanitarian mission," says Colonel Huggins.

I asked Griffin if he'd like to talk about the Najaf battle and all his pictures in a video interview. We borrowed some plastic chairs from an Internet cafe on the base, found an abandoned tent that was far away from the noise of the helicopter landing pad, and talked for 26 minutes.

He didn't say much about why he had joined the Army—for all the reasons printed on the recruiting posters, he offered. He'd been a rebellious kid, the kind that his junior high school assistant principal was happy to see move to high school so he could stop sticking him in detention. Griffin ran away from home several times, too, once waiting a month to call his father, telling him he was living in the attic of a martial arts studio. He met his wife while he was jogging in Pasadena, Calif. ("I know it sounds corny," he told her, stoping in the middle of the sidewalk, "but you look really beautiful.") They were married in 1994. Looking for excitement, he became a paramedic in the not-so-nice parts of Los Angeles, where he was shot at for the first time. But it was in the military that he found a new purpose and direction; he joined the National Guard in 1999 and, finding that too slow, went on active duty in July 2001.

In his first Iraq tour, Griffin spent time in Mosul and Tal Afar. He earned his chops kicking down doors and chasing bad guys, adventures that he documented in a journal on his laptop. He even won a Bronze Star with V for valor for saving the lives of three American and two Iraqi soldiers after an ied attack in Tal Afar.

"When I got to the top of the vehicle, I saw Sgt. Gordon's right leg hanging on by skin only ... As we were still taking heavy small-arms fire Doc and I were pulling out our First Sergeant, whose legs had both been broken by the powerful blast. As soon as we handed him down we began to treat Sgt. Gordon by applying a tourniquet to his nearly severed leg and then handed him down. When I climbed down from the vehicle to assess PFC Rosenthal, I noticed that his face had been severely burned, so I thought, but it was merely the soot from the blast. As soon as I knelt down to cut his pants off to assess his wounds, asphalt began chipping all around us due to the small-arms [fire] getting closer ... Once at the front of the vehicle, we began taking heavy fire from a mosque off to our east and there was just nowhere else to take cover. Luckily, our Commander's vehicle approached the wreckage and we immediately loaded all the casualties and they were brought back to [Forward Operating Base] Sykes."

His war experiences fueled his obsessive reading. "Philosophy has kept me grounded in conjunction with the things that I have seen in my life that have changed me drastically," he told me. His family and friends joke that they'd ask Griffin to send them reading lists before seeing him just so that they could keep up with his conversations. "He would come into the store and regularly drop a few hundred dollars on books," says Michael Smythe, the manager of Griffin's favorite bookstore, who spoke at his funeral.

While the books were helping him think, events on the ground were changing him. "I can't wait to see you guys," he wrote home to his father in April 2005. "I will not be right for sometime when all this is over. I have done some things that will haunt me for a long time to come and pray that G-d will forgive me for having done them. Let's just say that the enemy can start to appear in the very people that you are here to 'help.'"

Many of the soldiers in Iraq carry cameras. One in the 2-3 went into battle with a Canon slr strapped in a pouchlike holster on his thigh. Griffin went through three digital cameras during his two tours, once running through a hail of enemy bullets to fetch one he'd dropped in the sand. "I hope, in the long run, that those pictures will help this generation to deal with whatever will have to be dealt with in the aftermath of this thing," says Huggins, reflecting on the thousands of personal pictures that his soldiers have taken. "They will certainly never forget the things that they have done here."

When Griffin was home in Fort Lewis, Wash., between his first and second deployments, Diana would sometimes find her husband with head lowered, crying. "He had a slightly harder heart when he came back," she said. "He wanted to appear unchanged by what he had seen. All I could do was keep telling him that it was OK either way."

Griffin was first deployed with a Stryker unit from the 1st Brigade, 25th Infantry Division. On Jan. 3, 2005, in Tal Afar, his unit was called from its base in an old castle to head into the city to deal with the body of an Iraqi policeman's son, who had been beheaded.

"We took some Iraqi cops to the scene and did in fact see a headless body with the head carefully stacked on top of the chest with the body lying flat on the ground. The police officers (3) went up to the body to identify it while security was maintained for them by us. Before they got within 8 ft. of the body, the body exploded and killed one while injuring severely the others ... We took the torso back to the castle where we have been for awhile and had to unzip the body bag so that other family members could identify the lower half by the shoes he was wearing."

"Later in the day, the Iraqi police, who were family members of the destroyed body, began to drink heavily and one of them (Ali) started shooting randomly into the crowded traffic circle below the castle. We watched as he killed a 17 yr. old girl, a 7 yr. old girl and a 28 yr. old male. We could not intervene as this was happening for very complex reasons. This has been one of the most horrific days of my entire 34 yrs. of living on this earth ... I am stupefied and stand in tragic awe in the face of this carnage, what could I possibly say? Where was God today?"

He often wrote about God in his E-mails home. He'd been a part-time pastor at a California Baptist church once, giving sermons on Wednesday nights. He'd knocked on the door of a church shortly after he met his wife in 1992. "I'd like to be saved," he'd said. In January, he asked his wife to send him a copy of the Koran, because he wanted to read about the Muslim faith. But in early March of this year, he told me that he'd stopped attending church. "I started studying philosophy and became an atheist," he said. "I'm still trying to contemplate God, but it is kind of hard here." Ten days later, on his birthday, he called home. "He was remarkably calm," recalled his father. "The things he has seen in war and the fact that he read so deeply in philosophical and theological issues led him to be often conflicted internally about God. He said that he reconciled his conflicts and that he was ready anytime God called him. Not the statement of an atheist."

Whatever his personal convictions, the memories of Najaf and other missions in early March were becoming a heavy piece of dangle. While embedded on March 5, I followed Charger Company on another raid that Griffin recounted in his journal. The platoon entered the home of a family whose only crime was having names similar to those of wanted insurgents.

"I noticed the mother attempting to breast feed her little baby and yet the baby continued to cry. [The interpreter] who is a certified and well educated doctor of internal medicine educated in Iraq, told me that the mother, because she was very frightened by our presence, was not able to breast feed her baby because the glands in the breast close up due to sympathetic responses to fear and stressful situations. I then tried to reassure the mother by allowing her to leave the room and attain some privacy so that she could relax and feed her child. I felt something that had been brooding under the attained callousness of my heart for some time."

"My heart finally broke for the Iraqi people. I wanted to just sit down and cry while saying I'm so, so sorry for what we had done. I had the acute sense that we had failed these people. It was at this time, and after an entire year of being deployed and well into the next deployment that I realized something. We burst into homes, frighten the hell out of families, and destroy their homes looking for an elusive enemy. We do this out of fear of the unseen and attempt to compensate for our inability to capture insurgents by swatting mosquitoes with a sledge-hammer in glass houses."

It was weeks later and back in the states that I realized that Griffin was the only soldier I had interviewed at any length with the video camera. Taking the camera along was just an experiment with multimedia reporting, after all. In the end, Griffin was only briefly mentioned in a story about the Stryker unit raids that appeared in the magazine. "Every night is something different," he's quoted as saying, while sitting in the back of his eight-wheel Stryker vehicle. "The uncertainty is one of the hardest things to deal with."

On March 23, I received an E-mail from Capt. Steve Phillips, the commander of Charger Company. Diana Griffin, he wrote, had bought out three stores' worth of magazines when her husband's quote appeared in print. "She called my wife several times to brag about how her husband was in the news," Phillips wrote. "I don't know if you remember him, but he was with [the] platoon the night you chased around for the 5 individuals that were fleeing us. Darrell was shot and killed two days ago when we were returning from our new area of operations within Sadr City."

Snipers are an infantryman's worst nightmare—an unseen enemy who can kill with ease. Even worse, insurgents these days have taken to videotaping kills videos that are sometimes broadcast on Iraqi satellite television. "We have been the deepest conventional force in Sadr City in the past 2 years I believe," Phillips wrote. "It is tense and it is a tough mission." Griffin was the first soldier from his unit killed during this combat deployment.

There was an E-mail message from Diana Griffin in my in box as well. "I was wondering if you have anything more of his interview [whether] you taped him or wrote it down that I may have, and also any pictures." I sent copies of the interview and the pictures to his family, and agreed to say few words at the funeral.

The bullet that ended his life also deprived him of an open-casket funeral. The ceremony was held at a large church in Porter Ranch, Calif., not far from his final resting place, the National Cemetery in downtown Los Angeles, in front of about 150 mourners. The local television station was there; so were members of the Patriot Guard Riders, a group of former servicemen who voluntarily escort military funerals to protect families from religious zealots who protest such things. Indeed, as the funeral procession made its way along the freeway from the church to the cemetery, a Toyota pickup swerved toward the hearse, beeping its horn with the driver's hand extending his arm with his thumb down.

The often distant branches of Griffin's family came together for the first time in years. His father sat modestly dressed next to Diana, who wore black. There were other family members there, too, some buttoned down, others with tattoos and long hair. And Darrell's sister, who, like her brother, excels in martial arts.

His remains lie under a sliver of white marble in the veterans' cemetery. Despite requests from his family members, the Army erased Griffin's laptop hard drive before returning it to them. It's done for security, officials said, but it also erases pictures and writings. Deletions are done by the military on a case-by-case basis, "but a lot of people buy recovery software and get some of the files back," an Army official offered. The Department of Defense also recently issued new regulations that, in practice, may severely limit soldiers' E-mailing and blogging. "[I] believe that readers should know the situation as it really is over here without any partisan interpretation of the facts," Griffin once blogged to a MySpace group. "Perception must not be reality; reality must stand on its own merits good or bad."

Darrell Griffin Sr., an accountant who also runs several business ventures, is compiling his son's writings into a book and hopes to travel to Iraq to see where his son died. "My emotions have [been] on a roller coaster going from extreme anger, to sadness, to helplessness, to acceptance to confusion and then all over again," he wrote me five days after his son's death. And the elder Griffin has been pressed by many of his friends and colleagues in Southern California to join the ranks of the antiwar movement and use the story of his son's death to help end the war. "They just don't seem to understand or accept that my son loved the Army—that the Army saved him in many ways—and that the thing he hated the most was politics getting in the way of finding real solutions for the Iraqis."

This month, his son-in-law's National Guard unit was activated for deployment to Iraq. In the coming months, he expects his grandson, a Marine medic, to go there as well. "There should be a limit on how much of this a family is asked to bear," he says.

Diana Griffin is moving from Fort Lewis, Wash., to be closer to her family in Southern California. And she remembers the chaplain coming to the door. "The President of the United States ... " he began. That's where her memory of the event stops. By her bedside, she still keeps a book on the 19th-century Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard that her husband hadn't finished reading. She didn't speak at the microphone to the assembled mourners at the funeral, but after the echoes of the graveside 21-gun salute faded into the din of the nearby freeway, she said this: "Today, Darrell has come home on his shield."

Charoltte Cathy Miller I agree with you 100%.

I was taught as a child that if we didn’t defend other countries that we would one day lose our own freedom’s z. That is why my family served in the military because they have seen how other countries have lost their freedom in their countries!

Leave a comment