Does The Pain Scale Work? What Does It Really Tell A Health Care Professional? Who Developed It?

Does The Pain Scale Work? What Does It Really Tell A Health Care Professional?

Understanding The Pain Scale: An Overview

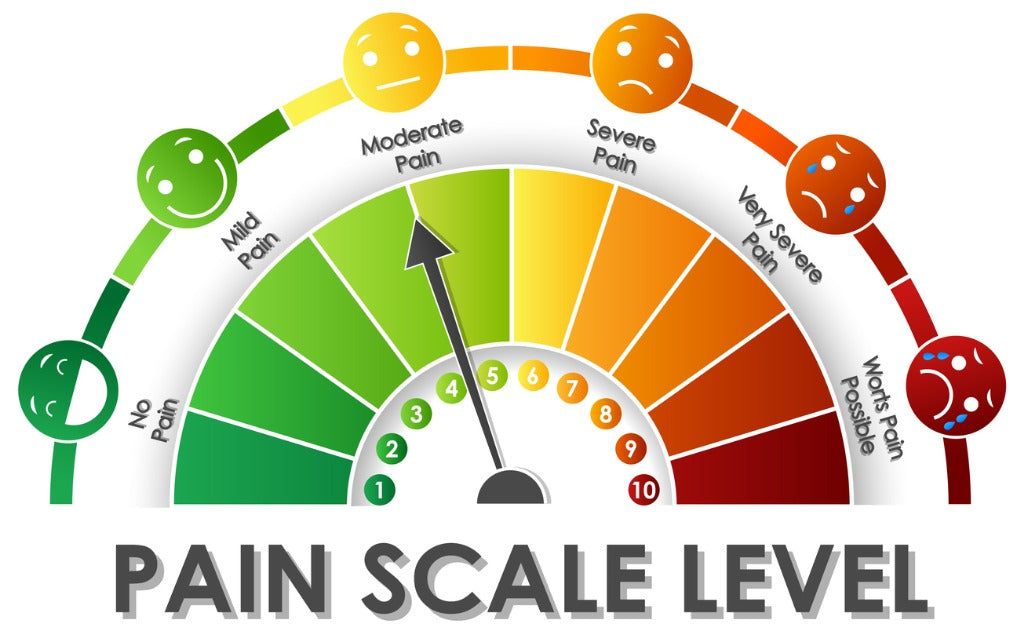

The pain scale, often represented numerically or visually through a series of faces, serves as a crucial tool in healthcare for assessing patient discomfort. Developed to provide a standardized method for patients to communicate their pain levels, the scale transcends subjective descriptions that can vary widely among individuals. Typically ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain), it allows healthcare professionals to gauge the intensity of a patient's experience and tailor treatment approaches accordingly.

While the origins of the pain scale can be traced back to various researchers and institutions, one significant contribution came from Dr. Melzack and Dr. Wall in the 1960s with their gate control theory of pain. This theoretical framework underscored how psychological factors influence pain perception, leading to more nuanced assessments in clinical settings.

However, while the pain scale is invaluable for initiating conversations about discomfort, its limitations must also be acknowledged. It primarily captures intensity without accounting for other dimensions such as emotional responses or functional impact on daily life. Thus, while it provides essential information for diagnosis and treatment planning, healthcare professionals must integrate this data with comprehensive patient evaluations to achieve holistic care outcomes.

Ultimately, understanding both its utility and constraints is key to fostering effective communication between patients and providers regarding pain management strategies.

The Development Of The Pain Scale: Historical Context

The development of the pain scale is rooted in a growing recognition of the subjective nature of pain and the need for effective communication between patients and healthcare professionals. Historically, pain was often dismissed or inadequately addressed due to its intangible nature, leading to a lack of standardized measures for its assessment. The early 20th century saw some initial attempts at quantifying pain, but it wasn’t until the latter part of the century that significant strides were made.

In the 1970s, researchers began to focus on patient-reported outcomes as vital components of clinical assessment. One notable development was the creation of numerical rating scales (NRS) and visual analog scales (VAS), which allowed patients to convey their pain levels more effectively. These tools aimed to bridge the gap between subjective experiences and objective medical evaluation, providing healthcare professionals with a clearer understanding of a patient’s condition.

The introduction of standardized scales also coincided with shifts in medical philosophy that emphasized patient-centered care. Among those who contributed to this evolution were Dr. Bonnie McCarberg and Dr. Richard E. Fine, who played pivotal roles in promoting comprehensive approaches to pain management through better assessment tools.

As these scales gained acceptance within clinical settings, they transformed how healthcare providers approached treatment decisions, ultimately enhancing patient care by recognizing pain as a critical aspect of health that deserves attention and validation.

How The Pain Scale Is Measured: Different Approaches

The measurement of pain is inherently subjective, leading to the development of various approaches to gauge its intensity effectively. One of the most common methods employed is the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), where patients are asked to rate their pain on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 representing the worst possible pain. This straightforward numerical approach allows healthcare professionals to quickly assess a patient's condition and track changes over time.

Another widely used method is the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), which presents patients with a line or continuum marked at one end with "no pain" and at the other with "worst pain imaginable." Patients indicate their level of discomfort by marking a point on this line, allowing for nuanced interpretations of their experience. Additionally, some practitioners use descriptive scales that incorporate words like “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe” alongside numeric values.

Beyond these scales, more comprehensive assessments consider emotional and psychological factors associated with pain. Instruments like the McGill Pain Questionnaire provide deeper insights by exploring sensory and affective dimensions of pain through descriptive adjectives. Ultimately, while these various approaches can offer valuable information about a patient's experience, they also underscore the complexity of measuring something as personal and multifaceted as pain.

What The Pain Scale Reveals To Healthcare Professionals

The pain scale serves as a vital communication tool between patients and healthcare professionals, providing insights that extend beyond mere numerical values. When patients indicate their level of pain on a scale, they convey not just intensity but also the impact of that pain on their daily lives and overall well-being. This subjective measure allows healthcare providers to gauge the effectiveness of treatments, understand the severity of a condition, and tailor interventions accordingly.

Healthcare professionals recognize that the pain scale can highlight discrepancies between a patient’s reported experience and observable signs. Such differences may prompt further investigation into underlying issues or psychosomatic components affecting the patient's health. For instance, a high self-reported pain score with minimal physical findings may suggest chronic conditions like fibromyalgia or psychological factors such as anxiety or depression.

Moreover, the pain scale assists in tracking changes over time. By regularly assessing a patient's self-reported levels of discomfort during consultations, clinicians can identify trends that inform long-term care strategies. Ultimately, while it does not encapsulate all aspects of an individual's experience with pain—such as emotional or social dimensions—the pain scale remains an essential component in creating holistic treatment plans tailored to each patient's unique needs.

Limitations And Criticisms Of The Pain Scale

The pain scale, while a valuable tool in clinical settings, is not without its limitations and criticisms. One primary concern is its subjective nature. Pain is inherently a personal experience, influenced by various factors including psychological state, cultural background, and past experiences. This subjectivity can lead to inconsistencies in how patients interpret and communicate their pain levels. For example, two individuals might rate their pain the same on a numeric scale despite experiencing it differently, potentially leading to misjudgment of treatment needs.

Additionally, the simplicity of many pain scales may inadequately capture the complexity of chronic pain conditions or multifaceted symptoms. Patients with chronic pain often experience fluctuations in intensity and quality that a static numerical value fails to represent effectively.

Furthermore, reliance on the scale can sometimes overshadow other critical aspects of patient assessment. Health care professionals may focus too heavily on achieving specific numbers rather than considering broader context—such as functional abilities or emotional well-being—when devising treatment plans.

Finally, there are concerns regarding potential biases in interpreting results. Health care providers may unconsciously project their own biases onto patients’ reports of pain, which could skew understanding and management strategies. Ultimately, while the pain scale serves as a useful communication tool between patients and providers, it should be employed alongside comprehensive assessments for effective care delivery.

The Future Of Pain Assessment In Healthcare

The future of pain assessment in healthcare is poised for significant evolution, driven by advancements in technology and a deeper understanding of pain as a complex biopsychosocial phenomenon. Traditional pain scales, while useful for gauging subjective experiences, often fall short in capturing the full spectrum of individual pain experiences. Emerging tools, such as wearable devices equipped with biosensors, promise to offer real-time data on physiological responses associated with pain.

These technologies could complement traditional self-report methods by providing objective measurements that reflect changes in heart rate, skin conductance, and muscle tension.

Moreover, the integration of artificial intelligence into pain management systems holds great potential. AI can analyze vast amounts of patient data to identify patterns and predict responses to various treatments. This personalized approach enables healthcare professionals to tailor interventions based on individual needs rather than relying solely on standardized assessments.

Additionally, there is a growing recognition of the importance of emotional and psychological factors in pain perception. Future assessments may incorporate validated questionnaires that evaluate mental health alongside physical symptoms, fostering a more comprehensive understanding of each patient's unique experience.

As the landscape shifts toward more holistic approaches to healthcare, the evolution of pain assessment will likely enhance communication between patients and providers. Ultimately, this progress aims not only to improve treatment outcomes but also to foster empathy and understanding within clinical settings.